By this time, information about the

need to apply professional skepticism for domestic auditors is indicated in the

International Standards on Auditing (ISA), which since 2003 have been adopted

in Ukraine as national.

2.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Due to the long absence of national

legislation on the nature and necessity of professional skepticism in the field

of independent audit, in Ukraine there are virtually no scientific developments

related to theoretical and practical aspects of the use of skepticism in the

audit profession, except for research Makarevich (2017), Redko (2020),

Shestakova (2014).

However, the analysis of scientific

works of foreign scholars shows a fairly thorough coverage in scientific

circles of the auditor's professional skepticism, which confirms the importance

and fundamentality of the concept of professional skepticism for the

development of the audit profession and ensuring high audit quality.

Hurtt (2010) suggests that

professional scepticism should be a multidimensional individual characteristic,

in particular, as an individual characteristic, professional scepticism can be

both a character trait (relatively stable, stable aspect of personality) and a

state (temporary state caused by situational variables). The researcher

developed a 30-point scale to be able to measure the level of individual

professional scepticism based on characteristics derived from auditing,

psychology, philosophy, and consumer behaviour research standards.

Quadackers (2009) in his

dissertation conducted a study of the attitude of sceptical characteristics of

the auditor to the judgment and decision-making of auditors. The researcher

explored the three most widely recognized sceptical characteristics:

interpersonal trust (and factors analysed by interpersonal trust factors),

suspension of judgment, locus of control (a concept introduced by American

psychologist Rotter and characterizes the subjective perception of localization

of causes of behaviour or leadership in yourself or others).

Nolder and Kadous (2018) propose a

dual concept of professional scepticism (as a way of sceptical thinking and as

a sceptical attitude) in order to develop measurement indicators for each

component. The inclusion of a scepticism component broadens the notion of

evaluating evidence by adding auditors' sense of risk as well as their belief

in risk, and this, scientists say, will improve the predicted "strength of

scepticism" in gathering audit evidence.

Jcohen, Dalton and Harp (2017)

investigated the impact of auditor qualities that determine the two most

influential points of view on an auditor's professional scepticism: a neutral

point of view and a questionable point of view. Researchers surveyed 176

auditors and concluded that a neutral view of professional scepticism has a

positive effect on the career growth of audit professionals due to a higher

level of perception of partner support, while doubts have a negative effect on

the career of auditors due to the low level of perception of partner support.

Researchers assess this fact as a worrying dilemma for the audit profession:

although sceptics can improve the quality of auditing, they are less likely to

remain in the profession.

Rodgers, Mubako and Hall (2017)

believe that the exchange of experience plays an important role in increasing

the professional scepticism of auditors. The results of the study are important

because they illustrate the importance of knowledge transfer to facilitate

auditors' use of appropriate professional scepticism when planning auditors'

participation in the task.

Researchers Hussin and Iskandar

(2015) confirmed the suitability of using the 30-point Hurtt’s scepticism scale

Hurtt (2010) to determine the level of professional scepticism used by

Malaysian auditors. In addition, the study found that there are only five signs

of professional scepticism in the Malaysian environment, in contrast to the six

traits proposed by Hurtt (2010). Rejection of judgments, according to

researchers, may be irrelevant for Malaysian auditors, as respondents require

more time to make audit decisions and may delay working with the audit.

Redko (2020) arely notes that

“professional scepticism is what is manifested in the work of the auditor; it

is only the concentration of a certain critical thinking in the course of

professional activity. Outside of professional activities, scepticism is a

person's choice”.

Makarevych (2017) compares professional

scepticism with the auditor's suspicion, noting that “the auditor's suspicion

is not a personal attitude to the customer's management, but the basis of

professional behaviour. Only a sober look will help to properly assess the

situation and draw conclusions based on the information received".

Shestakova (2014) believes that

professional scepticism is a key factor in obtaining an objective critical

assessment of the reliability of the collected evidence by internal auditors.

3.

METHODOLOGY

124 questionnaires were distributed

to auditors in Ukraine in order to conduct empirical studies to determine the

level of professional scepticism of auditors. A total of 92 questionnaires were

received, accounting for 74% of responses. The study uses a questionnaire

method to determine the level of professional scepticism of participants on the

thirty questions identified by Hurtt (2010).

Hart's scale of professional

scepticism (Hurtt, 2010) consists of 30 questions, scored on a 6-point scale,

ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). 22 questions are

presented as positive statements; the remaining 8 questions are presented in

the form of reverse statements. The question, the scores of which should be

reversed are marked (r), and summed up with a negative sign.

The questionnaire aims to determine

the level of professional scepticism of the participant. Adding points leads to

measuring the degree of professional scepticism. The higher the scores is the

higher the level of professional scepticism. At the same time low scores

indicate a lower professional scepticism of the auditor.

4.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The need for professional skepticism

in audit is justified by the fact that the auditor, due to the nature of the

profession, must question the audit evidence, contradicting each other, the

reliability of documents, responses to inquiries, oral messages received from

management, since the auditor, despite his own opinion regarding the integrity

of management, should not be content with less convincing evidence.

Therefore, the application of

professional skepticism requires ongoing curiosity as to whether the

information received and audit evidence suggests that a material misstatement

due to fraud may exist. This includes considering the reliability of the

information to be used as audit evidence and, if necessary, controls over its

compilation and storage. Through the characteristics of fraud, the auditor's

professional skepticism is especially important when considering the risks of

material misstatement due to fraud (ISA, 2016-2017).

ISA requires the auditor to exercise

professional judgment and maintain professional skepticism throughout the

planning and execution of the audit, in particular:

·

identify

and assess the risks of material misstatement as a result of fraud or error,

based on the understanding of the business entity and its environment,

including the internal control of the business entity;

Obtain acceptable audit evidence

about the existence of material misstatements by designing and implementing

appropriate responses to the assessed risks.

·

form

an opinion on the financial statements based on the conclusions drawn from the

obtained audit evidence (ISA, 2016-2017).

If the auditors have no reasonable

grounds to believe that the documents are false, then he can trust them.

However, if there are doubts about the reliability of the information,

especially if the auditor has a suspicion of possible fraud, he should conduct

further investigation, determining the necessary audit procedures.

An audit performed in accordance

with ISA rarely involves the verification of the authenticity of documents; the

auditor does not have such training and is not expected to be an expert in

authentication. However, if the auditor identifies conditions that lead him to

believe that the document may be authentic or that the conditions in the

document have been changed but such information has not been disclosed to the

auditor, possible procedures for further investigation may include: direct

confirmation by a third party; using the work of an expert to assess the

authenticity of the document (ISA 2016-2017).

The Law of Ukraine "On Auditing

Activity" dated April 22, 1993 did not contain a definition of

professional skepticism, which, in our opinion, was a significant gap in the

domestic legislation that regulated audit activity.

The new Law "On the audit of

financial statements and auditing activities" dated December 21, 2017

(hereinafter - the Law), which is aimed at bringing domestic legislation in the

field of independent audit with European standards, contains the definition of

professional scepticism, given in Art. 6: auditors and audit entities are

required to comply with the principle of professional scepticism in the

provision of audit services, which provides for the assumption of the

possibility of material misstatement of information disclosed in the financial

statements, due to facts or behaviour identified during the audit, indicating

violations, including fraud or error, despite the previous experience of the

auditor and the subject of the audit activity on the honesty and decency of the

officials of the legal entity whose financial statements are being audited (Law

of Ukraine "On the audit of financial statements and audit

activities").

Analysing the definitions of

professional scepticism given in Ukrainian legislation, it should be noted that

it is the broadest of all those presented in the audit standards. In this case,

we are talking about the principle of professional scepticism.

In general, a principle (lat.

Principium - beginning, foundation) is the main starting point of any

scientific system, theory, ideological direction (http://sum.in.ua/s/pryncyp).

That is, the auditor must always

admit the possibility of material misstatement of information as a result of

error or fraud, using his own critical thinking as the basis for collecting and

evaluating evidence obliges him to question the written and oral statements of

the client's management personnel, despite the honesty of his management and

previous experience of the auditor.

In addition, the Law states that the

auditor and the subject of the audit activity should critically and doubtfully

approach the fair value estimates applied by the legal entity, the decrease

(restoration) of the usefulness of assets, collateral (reserves) and future

cash flows affecting the assessment of the ability of the legal entity continue

their activities on an ongoing basis (Law).

Redko (2020) believes that "the

professional skepticism of the auditor is the basis of his professional

independence, and if the auditor is really independent, then during the audit

he constantly corrects something, clarifies, changes something." Such

actions occur as a result of the auditor's application of his own critical thinking

in relation to the information he receives as audit evidence from the client

during the audit process.

Using the principle of professional

skepticism means that the auditor avoids information bias by developing his own

critical thinking, based on the presence of doubts in the perception of a

particular situation. This enables the auditor to draw conclusions that will be

based on an objective perception of the information received, rejecting

subjective factors.

Makarevich (2017), for example,

believes that “different levels of verification of the auditor's work within

the company make it possible to look at the situation from different angles and

analyse the data in detail, to avoid selective perception. In order to minimize

group thinking, it is logical to include internal experts from the client's

market in the team, which will help to get an alternative view of the business

from the side of the sector practitioner, and not just the financier.

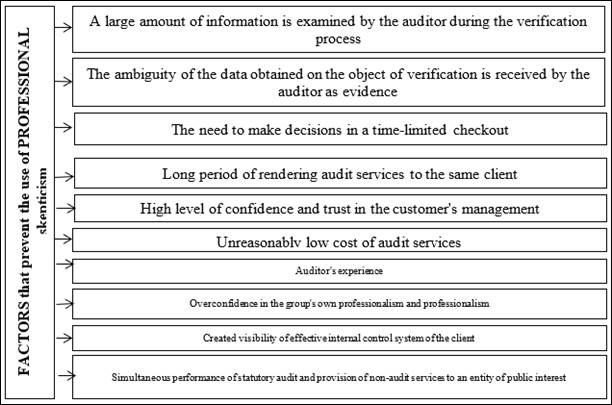

The application of professional

skepticism by auditors is facilitated by the quality control system of audit

services, which is being implemented at the audit firm and consists of the

following elements: assignment; ethical requirements, monitoring; human

resources; management responsibility for organizing quality control; acceptance

of the task and the continuation of cooperation with the client, and the

implementation of specific tasks.

The study conducted by Khorunzhak, et

al. (2020) shows that in Ukraine there is an objective need and favourable

conditions for the development of not only the quality control system of

auditing and auditing activities, but also good prerequisites for its

improvement of quality of audit services.

The quality control system

implemented in the audit firm can help auditors to increase the effectiveness

of the use of professional skepticism for the employer to use such methods (Figure

1).

Figure 1: Methods for improving the

effectiveness of using the professional skepticism of the auditor through the

quality control system of the audit firm

Source:

compiled by the author based on (Information Note)

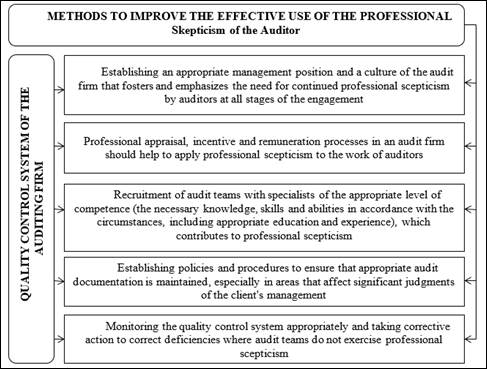

The research conducted by the author

on the essence and practical aspects of the use of professional skepticism of

the auditor made it possible to highlight the factors that prevent its use in

audit practice, summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Factors

impeding the application of professional skepticism of the auditor

Source:

generated by the author

Long-term interaction of the auditor

with the same customer negatively affects professional skepticism, because over

time, as a result of long-term relationships, the auditor weakens his critical

thinking during the audit, begins to trust more information provided by the

client's financial statements audit management. Therefore, there are restrictions

on the duration of the provision of audit services to the same company.

So, in part 1 of the Article 30 of

the Law (2017) states that the continuous duration of the assignment for the

statutory audit of financial statements for the subject of audit activity

cannot exceed 10 years.

Ball, Tyler and Wells (2015)

conducted empirical studies on the relationship between audit quality and the

term of office of the auditor, which would confirm the arguments in favour of

the rotation of auditors provided for by regulations. The term

of the auditor is measured both by taking into account the duration of the

relationship between the key audit partner and the management of the audit firm

(personal relationship), and taking into account the duration of the interaction

of the audit firm with the client. As a result of a study of 266 public

Australian firms, the researchers concluded that rotation of key audit partners

can bring qualitative benefits, but the rotation of audit firms is only an

additional cost for quality.

Bandyopadhyay, Chena and Yub (2014)

investigated the implications for audit quality of China's mandatory rotation

of audit partners every five years, which came into effect in 2014. The

scholars found that audit quality improved over the three years following the

change of audit partner in the provinces of China where there was a low level

of concentration of the audit market, but this improvement was not noticeable

in jurisdictions where the audit market was dominated by several large audit firms.

The Law (2017) establishes

restrictions on the simultaneous provision of mandatory audit services of

financial statements and such non-audit services to enterprises of public

interest: preparation of tax reports, calculation of mandatory fees and payments,

representation of legal entities in disputes on these issues; consulting on

management, development and support of management decisions; accounting and

financial reporting; development and implementation of internal control

procedures, risk management, as well as information technology in the financial

sector; provision of legal assistance in the form of: services of a legal

adviser to ensure the conduct of business activities; negotiating on behalf of

legal entities; representation of interests in court; staffing of legal

entities in the field of accounting, taxation and finance, including services

for the provision of personnel who make management decisions and are

responsible for preparing financial statements; valuation services; services

related to raising finance, distribution of profits, development of an

investment strategy, except for services to provide confidence in financial

information, including the implementation of procedures necessary for the

preparation, discussion and issuance of letters of confirmation in connection

with the issue of securities of legal entities.

As a result of the reforms, the

volume of non-audit services that can be provided to subjects of public

interest due to problems with independence has decreased, however, according to

Francis (2004), the quality of the audit will always be somewhat questionable

if other services are provided next to the audit, as they may jeopardize

objectivity and skepticism of the auditor. In this regard, public confidence in

the quality of audit can be increased by prohibiting the provision of all

non-audit services to subjects of public interest.

Referring to Hurrt's model of

skepticism (Hurtt, 2003), which has received a significant amount of positive

feedback from academics, and on the basis of which the level of professional

skepticism of auditors has been repeatedly studied (Fullerton & Durtschi, 2004; Quadackers,

2009; Hussin & Iskandar, 2015), we note that it contains six signs of

professional skepticism of the auditor of asking questions (the ability to

doubt) rejection of judgments; search for proven facts; understanding of

information received in the process of communication; confidence; certainty.

Later Hurtt developed the Hurtt

scale of professional scepticism (Hurtt, 2010), which consists of 30 questions,

scored on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly

agree). 22 questions are presented as positive statements; the remaining 8

questions are presented in the form of reverse statements. The question, the scores

of which should be reversed are marked (r), and summed up with a negative sign.

The questionnaire, which is

presented in Table 1 aims to determine the level of professional scepticism of

the participant. Adding points leads to measuring the degree of professional

scepticism. The higher the scores is the higher the level of professional

scepticism of the auditor.

124 questionnaires were handed out

to auditors in Ukraine to determine the level of professional scepticism of

auditors. A total of 92 questionnaires were received, accounting for 74% of the

responses.

The results of the questionnaire are summarized

in Table 2, allow us to assert that among the

92 Ukrainian auditors surveyed, the largest group is made up of auditors with

an average level of professional skepticism - 58% (53 people) with a high level

of professional skepticism - 29% (27 people), and the least numerous group with

a low level of professional skepticism - 13% (12 people).

Table 1: Hurtt scale of professional

skepticism (Hurtt, 2010)

|

¹ ç/ï

|

Question

|

Bali *

(from 1 (strongly

disagree)

up to 6 (completely

agree))

|

|

1

|

I

often accept other people's explanations without further thought (r)

|

-2

|

|

2

|

I feel good

|

5

|

|

3

|

I'm

waiting to resolve the issue until I can get more information

|

6

|

|

4

|

I

am interested in the prospect of learning

|

6

|

|

5

|

I'm

interested in what makes people behave the way they do

|

4

|

|

6

|

I

am confident in my abilities

|

5

|

|

7

|

I

often reject allegations if I have no evidence that they are true

|

6

|

|

8

|

It

is interesting to reveal new information

|

6

|

|

9

|

I

need time to make a decision

|

5

|

|

10

|

I

tend to immediately accept what other people tell me (r)

|

-3

|

|

11

|

I'm

not interested in other people's behaviour (r)

|

-3

|

|

12

|

I'm confident

|

5

|

|

13

|

My

friends tell me that I usually have doubts about the things I see or hear

|

4

|

|

14

|

I

like to understand the reason for other people's behaviour

|

4

|

|

15

|

I

think the training is exciting

|

6

|

|

16

|

I

usually accept things that I see, read or hear as true (r)

|

-3

|

|

17

|

I'm not sure (r)

|

-2

|

|

18

|

Usually

I notice a discrepancy in the explanations

|

5

|

|

19

|

Most

often I agree with what others in my group think (r)

|

-3

|

|

20

|

I

don't like to make quick decisions

|

4

|

|

21

|

I trust myself

|

5

|

|

22

|

I

don't like to make decisions until I've reviewed all the available

information

|

5

|

|

23

|

I

like finding new knowledge

|

6

|

|

24

|

I

often find out about things I see or hear

|

5

|

|

25

|

It's

easy for other people to convince me (r)

|

-3

|

|

26

|

I

rarely think about why people behave in a certain way (r)

|

-3

|

|

27

|

I

like to make sure I review the most available information before making a

decision

|

5

|

|

28

|

I

like to try to determine if what I read or hear is true

|

5

|

|

29

|

I like learning

|

6

|

|

30

|

The

actions that people take and the reasons for these actions are fascinating

|

4

|

|

|

Together, points

|

90

|

* average

scores are given according to the results of a survey of 92 auditors

Table 2: The results of the

questionnaire survey on the scale of professional skepticism Hart (2010),

Ukraine

|

|

The level of auditors professional skepticism

|

|

High (from 124 to 100 points)

|

Medium (99 to 75 points)

|

Low (74 points and below)

|

|

Number of auditors

|

27

|

53

|

12

|

|

Average score for the group

|

109

|

87

|

64

|

Source:

Hart (2010)

It should be noted that the use of

the Hurtt’s scale of professional skepticism (Hurtt,

2010) to measure the level of professional skepticism of auditors in Ukraine is

quite acceptable both for conducting scientific research and for ensuring

quality control procedures for audit services both at the intra-firm level and

at the level of external control. quality control by regulators, which are

represented by the Quality Control Committee of the Audit Chamber of Ukraine

and the Quality Assurance Inspectorate of the Public Oversight Body of Audit

Activities.

5.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

So, the auditor should use professional

scepticism throughout the audit process, from the acceptance of the task to the

formation of the audit opinion in the audit report. Evidence of the auditor's

compliance with the principle of professional scepticism is his behaviour,

based on critical thinking and a special approach to the information provided

by management, which consists in the constant presence of doubts about its

reliability and the formation on the basis of this appropriate vision of the

number and type of audit procedures necessary to obtain sufficient and

acceptable audit evidence.

It is this approach to auditing that

encourages the auditor to be attentive and demanding of details that may

indicate the presence of risks of errors and fraud in the customer's financial

statements. The auditor should have a particular critical composition of the

mind that will encourage him to take due diligence in collecting audit evidence

without relying on the approval of management personnel.

The results of the survey of

Ukrainian auditors indicate a sufficient level of professional scepticism

possessed by auditors, contributes to their professional independence and high

quality of services provided. The use of the Hurtt’s scale of professional

scepticism (Hurtt, 2010) to measure the level of professional scepticism of

auditors in Ukraine is quite acceptable for ensuring quality control procedures

for audit services both at the internal level and at the level of external

quality control.

The studies carried out confirm the

feasibility of developing a separate working document for the auditor, which

should contain a list of questions, the answers to which would enable the head

of the audit team (the head of the audit firm responsible for the audit firm's

quality control system) to summarize information on the application of

professional skepticism by team members in the audit process. This will ensure

that the audit engagement was carried out with a high level of professionalism

and professional independence, as the use of professional judgment in the audit

is the responsibility of every auditor.

The working document should be

structured in the form of a questionnaire, which will contain a set of

questions regarding the auditor's actions, confirming the presence of his

critical thinking and doubts during the verification process and, as a result,

the corresponding adjustments are reflected in the reassessment of risks and

materiality, changes and clarification of the procedures for collecting

evidence, is displayed in the audit plan and program and related working

papers.

This is important because, despite

the fact that today, domestic regulators still do not check whether auditors

use professional scepticism in the process of providing services, however,

based on the fact that the principle of professional scepticism affects the

quality of audit, each subject of the audit activities that cares about their

own business reputation will position themselves as a professional who provides

services in accordance with the highest standards of the auditing profession.

This, in turn, implies the need to apply professional scepticism at every stage

of the audit.

REFERENCES

Antoniuk, O., Chyzhevska, L., & Semenyshena, N. (2019). Legal

Regulation and Trends of Audit Services: What are the Differences (Evidence of

Ukraine). Independent Journal of

Management & Production, 10(7),

673-686. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v10i7.903.

Ball, F. , Tyler, J., & Wells, P. (2015).

Is Audit Quality Impacted by auditor Relationships? Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 11(2), 166-181. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2015.05.002.

Bandyopadhyay, S.P., Changling. Ch., & Yingmin, Yu. (2014).

Mandatory Audit Partner Rotation, Audit Market Concentration, and Audit

Quality: Evidence from China. Advances

in Accounting, 30(1), 18-31. DOI: DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2013.12.001.

Bhattacharjee, S., & Moreno, K. K. (2013).

The Role of Auditors' Emotions and Moods on Audit Judgment: A Research Summary

with Suggested Practice Implications. Current

Issues in Auditing, 7(2), 1-8.

Boyle, D. M.; Carpenter, B. W. (2015).

Demonstrating Professional Skepticism. The

CPA Journal, 85(3), 31-35.

Brazel, J. F., Jackson, S. B., Schaefer, T. J.,

& Stewart, B. W. (2016). The Outcome Effect and Professional Skepticism. The Accounting Review, 91(6), 1577-1599.

Cohen, J.R., Dalton, D.W., & Harp, N.L.

(2017). Neutral and Presumptive Doubt Perspectives of

Professional Skepticism and Auditor Job Outcomes. Accounting, Organizations and

Society, 62, 1-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2017.08.003.

Coppage, R., & Shastri, T. (2014).

Effectively Applying Professional Skepticism to Improve Audit Quality. The CPA Journal, 84(8), 24.

DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor Size and Audit

Quality. Journal of Accounting and

Economics, 3(3), 183–199.

Fatmawati, D.,

Mustikarini, A., & Fransiska, I. (2018). Does accounting education affect

professional skepticism and audit judgment? J. Pengur, 52, 221–233.

Favere-Marchesi, M., & Emby, C. (2017). The

alumni effect and professional skepticism: An experimental investigation. Accounting Horizons, 32(1), 53-63.

Fei Gong, Y., Kim, S., Harding, N. (2014).

Elevating professional scepticism: An exploratory study into the impact of

accountability pressure and knowledge of the superior’s preferences. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(8),

674-694.

Francis, J.R. (2004). What do We Know about Audit Quality? The British Accounting Review,

36(4), 345-368. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2004.09.003

Fullerton, R., & Durtschi, C. (2004). The Effect of Professional Scepticism on the Fraud Detection Skills of

Internal Auditors. Available: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=617062.

Hardies, K., & Janssen, S. (2017). FAR Research Project:

Professional skepticism: a trending concept in need of understanding. Maandblad Voor Accountancy en

Bedrijfseconomie, 91, 274-280.

Hurtt, R., Brown-Liburd, H., Earley, C. & Krishnamoorthy, G. (2013).

Research on Auditor Professional Skepticism: Literature Synthesis and

Opportunities for Future Research. Auditing:

A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(1), 45-97.

Hurtt, R.K. (2010). Development of a Scale to Measure Professional Skepticism. Auditing: a Journal of Practice &

Theory, 29(1), 149-171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2010.29.1.149

Hurtt, R.K., Eining, M., & Plumlee, D.

(2003). Professional

Skepticism: A Model with Implications for Research, Practice and Education. Working paper. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hussin, S.A.H., & Sayed, I.T.M. (2015). Re-Validation of Professional Skepticism Traits. Procedia Economics and Finance, 28, 68-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01083-7.

Informatsiina Zapyska Dlia Audytoriv ¹10 (2013). Zberezhennia Profesiinoho Skeptytsyzmu ta yoho Zastosuvannia na

Praktytsi v Khodi Audytorskykh Perevirok. Nezalezhnyi

audytor, 3(14), 2-8. Available: http://n-auditor.com.ua/components/com_jshopping/files/demo_products/Nezalejniy_auditor_3_2013_.pdf

Khorunzhak, N., Belova, I., Zavytii, O.,

Tomchuk, V., & Fabiianska, V. (2020). Quality Control

of Auditing: Ukrainian Prospect. Independent

Journal of Management & Production,

11(8), 712-726. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v11i8.1229.

Kwock, B., Ho, R., & James, M. (2016). The effectiveness of

professional scepticism training for auditors in China: evidence from a

university in China. China Journal of

Accounting Studies, 4(2), 205-224.

Makarevych, A. (2017). Shcho potribno znaty pro

psykholohiiu audytora? Biznes. Available: https://nv.ua/ukr/biz/expert_author/makarevich.html. Access:

10 September 2020.

Mizhnarodni Standarty

Kontroliu Yakosti, Audytu, Ohliadu, Inshoho Nadannia Vpevnenosti ta Suputnikh

Posluh, part 1.

(2016-2017). Olkhovikova, O.L. Shulman,

M.K. (Transl.) Available: https://www.apu.net.ua/attachments/article/1151/2017_%D1%87%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8C1.pdf . Access: 12

September 2020.

Nolder, C.J., & Kadous, K. (2018).

Grounding the professional skepticism construct in mindset and attitude theory:

A way forward. Accounting, Organizations

and Society, 67, 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100299.

On the Audit of

Financial Statements and Auditing Activities: Law of Ukraine ¹ 2258-VIII (21 December

2017). Available: http://zakon2.rada.gov.ua /laws/show/2258-19. Access: 02

August 2020.

Pryntsyp. Slovnyk ukrainskoi movy. Akademichnyi tlumachnyi slovnyk (1970-1980). Avaible at: http://sum.in.ua/s/pryncyp. Access: 16 September 2020.

Quadackers, L. (2009). A Study of Auditors’

Skeptical Characteristics and Their Relationship to Skeptical Judgments and

Decisions. DOI: https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/42180914/complete+dissertation.pdf .

Redko, Yu.O. (2020). Professional skepticism: webinar. Available: https://youtu.be/AGZuCJkO04M. Access: 15 August 2020.

Rodgers, W.,

Mubako, G.N., & Hall, L. (2017). Knowledge

management: The effect of Knowledge Transfer on Professional Skepticism in

Audit Engagement Planning. Computers in

Human Behavior, 70, 564-574. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.069.

Rodrigues P.C.C., & Semenyshena N. (2019). Editorial Introduction. Independent Journal of Management &

Production, 10(7), 911-914. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v10i7.775.

Rodrigues,

P.C.Ch., Simanaviciene, Z.,

Semenyshena, N. (2020). Editorial

Volume 11, Issue 9. Independent

Journal of Management & Production, 11(9), 2542-2547. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.14807/ ijmp.v11i9.1424.

Sayed Hussin, S. A. H., Iskandar, T. M., Saleh,

N. M., Jaffar, R. (2017). Professional Skepticism and Auditors’ Assessment of

Misstatement Risks: The Moderating Effect of Experience and Time Budget

Pressure. Economics and Sociology,

10(4), 225-250. DOI:10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-4/17.

Semenyshena, N., Khorunzhak, N., &

Zadorozhnyi, Z.-M. (2020). The

Institutionalization of Accounting: the Impact of National Standards on the Development

of Economies. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 11(8), 695-711. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v11i8.1228.

Semenyshena, N., Sysiuk, S.,

Shevchuk, K., Petruk, I., & Benko, I. (2020). Institutionalism

in Accounting: a Requirement of the Times or a Mechanism of Social Pressure? Independent Journal of Management &

Production, 11(9), 2516-2541. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v11i9.1440.

Shestakova, O. (2014). Vidpovidalnist ta

Skeptytsyzm Vnutrishnikh Audytoriv v Otsintsi Ryzykiv Shakhraistva. Ekonomist, 2, 54-56. Available: http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/econ_2014_2_16. Access: 17 August 2020.

The International Forum of Independent Audit

Regulators (IFIAR) (2015). Report on 2014 Survey of Inspection Findings. IFIAR: Tokyo, Japan. Available

at: https://www.ifiar.org/?wpdmdl=2064. Access: 19 October 2020.

AUDITOR'S

PROFESSIONAL SKEPTICISM: A CASE FROM UKRAINE

AUDITOR'S

PROFESSIONAL SKEPTICISM: A CASE FROM UKRAINE